It’s been nearly a month since former President Ashraf Ghani fled and the Taliban took over Afghanistan. August 15, 2021, was only 24 hours, but to the Afghan people it felt like entire years of politics passed in a single day. We all knew the Taliban were likely to come to Kabul at any time, Mazar-e Sharif and Jalalabad had just become the last two major cities to fall to the group overnight. Throughout the morning, the city was gripped with panic, as people pictured the Taliban storming into the capital, guns blazing. Those fears went into overdrive when the rumors that President Ashraf Ghani had already fled began circulating well before Dr Abdullah Abdullah made the official announcement on Facebook.

Some relief came in the early afternoon, when the Taliban announced that they would not come to Kabul with violence. By the time they did enter the city, it was early evening and much of the capital had already been safely relegated to their homes. When Kabulis woke up on the morning of August 16, the city was already full of Taliban and their black-on-white flag. They stopped to talk to people. Asked to have their pictures taken and took selfies with curious passersby. But the city was largely empty, most shops and offices were closed.

As the days progressed, the number of Taliban visibly on the streets reduced. Most were seen traveling in the Rangers and Humvees that once belonged to the Afghan National Security Forces. However, Afghan social media was full of reports of house searches, abuses of people, including women, intimidation and even killings. There were similar reports coming from the provinces. However, most of those reports were difficult to prove and remained claims that few people could easily investigate.

Taliban government

When the Taliban did announce their “temporary” government on the evening of September 7, the people had already spent weeks living through a disconnect between what the Taliban said and how they behaved on the streets of Kabul and other cities. Though they promised to grant a “general amnesty” to all people, we saw the killings and abuse of protesters in Jalalabad, Kunar and Khost around the 102nd anniversary of independence. The first major ideological battle between the people and the Taliban was fought over the flag. Men, young and old, tried to raise the tricolor flag of the Islamic Republic, sometimes taking down the Taliban’s two-tone flag to do so. The protests did not end there. Women and girls in Kabul, Herat and Nimroz took to the streets to demand the right to work and a role in any future government. Those protests ramped up when Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, the deputy head of the group’s political office in Doha, said there “may not” be a place for women in the higher echelons of a Taliban government. A number of the female protesters claimed they had been allowed to return to work by the Taliban. In Herat, the demonstrators said they tried to speak to the Taliban leadership in the Western province, but that the leaders did not make time to meet with them and address their concerns. Protests continued in Kabul, Herat, Daikondi and Balkh, when the Taliban announced that they had overrun the Northeastern province of Panjshir, where the National Resistance Front, led by the son of slain jihadi commander, Ahmad Shah Massoud, was based, on September 6. Though telecommunications networks in the province were cut off by the Taliban in late August, Ahmad Massoud released a voice message saying “strangers” were involved in the battle for Panjshir. His statement came amid rumors that Pakistani helicopters and drones could be seen flying over the Panjshir valley between September 5 and 6. Those claims could not be independently verified, but those allegations, along with Massoud’s message, were enough to see the people launch anti-Pakistan protests across several of the nation’s provinces. Online video showed the Taliban using aerial fire to disburse the crowds, which in some cases had ballooned to hundreds of people. There were also reports that journalists for some of the nation’s largest private media outlets were imprisoned or had their equipment confiscated by the Taliban.

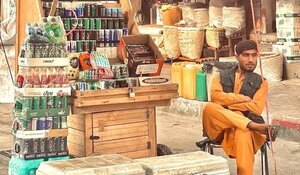

Now that the group has announced its caretaker government, full of long-time Taliban and Haqqani Network stalwarts, the group faces many challenges on its road to international recognition and restarting an Afghan government that had been largely stagnated since the waning days of the former Islamic Republic. Their primary concern will be restarting the economy. With no official government for weeks, many public offices remained shut for nearly a month, meaning hundreds of thousands of civil servants had no income. Further, they didn’t know if they would have jobs in the future. As banks remained closed for weeks, private offices and businesses could not afford to pay their staff. Many shut their doors as the Taliban took over and have yet to resume normal operations. When the banks did reopen, hundreds of people spent hours, even days, in line trying to get access to any amount of cash. However, with the International Monetary Fund, World Bank and US Federal Reserve having cut off the Afghan state from funds, banks and ATMs across the country would run out of cash on a daily basis. This is why the Taliban has repeatedly reiterated that they want foreign and Afghan investors to resume business as usual as soon as possible. They have also made overtures to other nations to restart their commercial endeavors in the nation.

Taliban and the threat of Islamic State – Khorasan (IS-KP)

The Taliban also have to deal with an ongoing threat from the so-called Islamic State. The group claimed responsibility for a series of bombings outside the Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul on August 26. Those bombings led to at least 175 deaths and more than 200 injuries, as thousands of people camped out near the airport’s military entrances, desperate to leave the country. The Taliban and CIA-backed former Afghan intelligence forces stationed outside the airport were accused of using aerial fire and plastic pipes to disburse crowds and keep people from entering the airport for weeks. The Taliban had promised order and security to the Afghan people, but the bombings and the group’s use of physical violence and intimidation to disburse crowds outside the airport, banks and protests, seemed to belie that assurance. When the group told female government workers not to return to work for some time, it was because they said they could not control how their fighters would react to women in the workplace. This was similar to the justification they used to keep women and girls from work and school during their five-year rule in the 1990s. Likewise, they ordered that female university students be taught by women or pious older men. This led to fears that public universities did not have enough female faculty or physical space to ensure the separation of the sexes, which would in turn keep more women from education in the country. Girls and boys have so far been able to resume their studies normally, as primary school has always been gender-segregated in the country. There was one sign of hope when the Taliban said female workers of the Ministry of Public Health could return to work as normal. In the early days after their takeover, Taliban members also visited female health workers in Kabul and assured them that they could continue their work.

Of course, for men and women, the possibility of returning to work hinges on the Taliban’s ability to run an orderly, functional government and to pay them their wages. However, with so much of their cabinet being full of purported religious leaders and scholars, there are serious questions about their capacity to handle the technical matters of running a state. (10. September 2021)